The temporal finiteness of human existence is only compensated by our ability to leave marks and collect data. However, we are so good at being curious that we use the past to explain the present and, if possible, the future beforehand. For example, paleoenvironmental reconstructions carried out from the collection of fossil material generate knowledge of biodiversity throughout geological time and are a source of scientific insights into the future.

However, when we do not have access to records of the past, what would become of us? There are 95,000 museums spread around the world according to UNESCO, 61.45% of which are in the countries that make up the G7 (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Great Britain, and the United States).

Museum collections around the world are being subject to historical repairs. Is it right for a sword belonging to the founder of an African empire to be on display in France? Can German researchers possessing a rare specimen from Cariri refuse to return the piece to its place of origin? In art, archaeology, meteoritics, and paleontology, there are constant disputes because they are excellent suppliers of unique specimens, and it is possible to note the centralization of such collections in colonizing countries.

To exemplify the confiscation of artifacts by colonizers to dismantle societies, Menezes & Álvarez (2019) state that “About African heritage, the state of works of art is indeed radical: the majority of the artistic production of the people of this continent (estimated at more than 80%) is practically all in Europe, whether in public museums or private collections. The loss of artistic heritage and, consequently, of these people’s identity, culture, and memory, is one of the main results of a colonial process that Western countries have carried out throughout history.”

It is worth noting that the history of humanity is essentially about relations of cultural domination and subjection, through armed conflict, territorial appropriations, and means of communication, among others. Therefore, the monopolization of historical-cultural heritage is the result of a colonial process carried out throughout human history by imperialist countries.

However, after the Second World War, according to Menezes & Álvarez (2019), the beginning of a movement to raise awareness about the historical claim was observed in Europe, which was experiencing its barbarism through Nazism. The obscurantism experienced in this period and the inhumane practices of a racist, misogynistic, and genocidal system, the persecution of art, and the destruction of historical-cultural heritage began a process of awareness about the expropriation and cultural domination of colonized countries, which is present, in the same way, in the extensive history of civilizing wars that have occurred throughout history.

It is possible to observe an increase in the return of collections to their countries of origin during recent years, some examples of which will eventually be presented throughout this text. However, it must be reflected that, even with the colonization process over, the legacy of colonialist thought still permeates the convictions of capitalist society. It is the beginning of a successful path but with a distant end.

The scientific monopoly on paleontological material

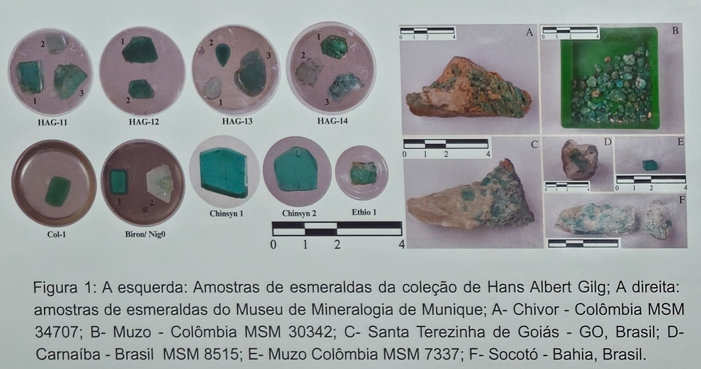

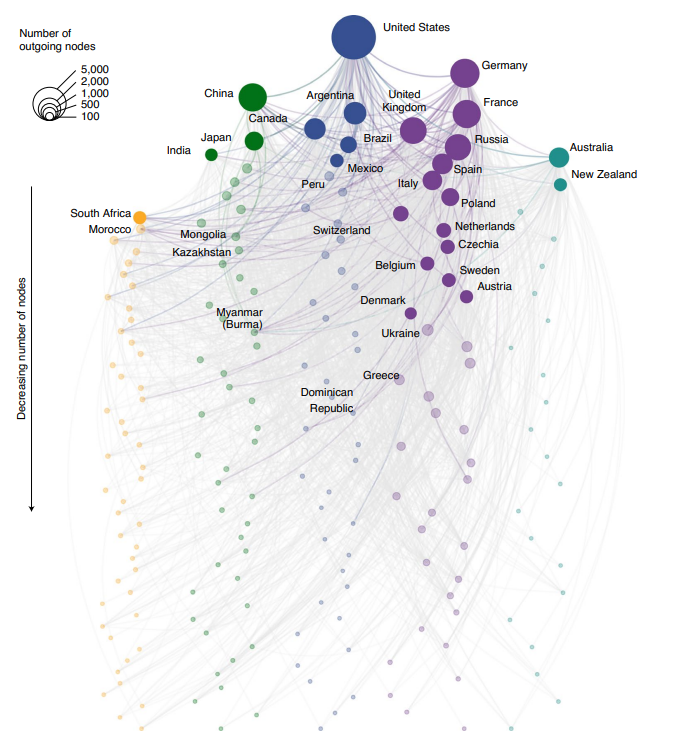

Colonialism is one of the main factors for the current scientific monopolization of paleontological materials and studies. It is discussed in a study carried out by Raja et al. (2021) on how colonial history and the current global economy directly influence the concentration of paleontological studies, which occurs mainly in countries in North America and Western Europe (Figure 1).

Natural sciences, throughout their history, have developed essentially through extractive methods and techniques. European extractivism took place through expeditions such as Charles Darwin’s Beagle, which traveled to South America and other continents, collecting the analyzed materials, which were transported, stored, and studied in Europe to later be displayed in its museums.

Currently, what has been practiced in the so-called “parachute science” or “scientific colonialism”, where a foreign researcher collects fossil material in an underdeveloped country, without even consulting local researchers, and violates national laws, as is the most recent Brazilian case on the Ubirajara Jubatus specimen that was presented in the article “Ubirajara belongs to Brazil!”. The current scientific monopoly is a legacy of colonialism, as already presented in this article, however, it is maintained through neocolonialist exploratory practices.

Illegal ivory trafficking

The trivialization of animal life to create artistic artifacts made of ivory is intrinsically linked to sacred art. Ivory became of great value to sculptors during the great navigations as it was durable and, when polished, beautiful, thus becoming part of the traffic in luxury artifacts in Europe initiated by the Silk Road.

However, the beauty of mere talismans is not a justification for the massacre of animals and the threat of extinction of African elephants, which led the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) to determine the force of ban on ivory trade on January 18, 1990. Only on December 31, 2017, however, was the ban on the legal ivory market ratified in China, a country believed to be the world’s largest consumer of the material. This attitude makes it possible to apprehend criminals like Yang Fenglan in 2019, accused of heading one of the largest illegal ivory trade groups in Africa.

Some say that poverty is the crucial factor in encouraging illegal hunting of wild animals, however, hunting is also seen as a source of prestige and status. The historical context must also be taken into consideration and as highlighted by Duffy et al. (2016) “… colonial legislation removed hunting rights from Africans to protect the sport hunting and safari industries for European colonizers”, which led to the criminalization of the livelihood of African families.

At the same time that illegal hunting of wild animals has been a source of financing for conflicts in African countries in the sub-Saharan region, wars have generated concentration camps with malnourished refugees who go hunting for their livelihood. Consequently, the issue of illegal hunting will not be resolved only with financial assistance, but with a broad study of social, economic, and political inequalities.

Assets repatriation

The Macron government started to adopt new policies regarding the return of historical artifacts looted in former French colonies due to strong popular pressure. In 2019, the French government returned a historic 19th-century sword to Senegal. This sword belonged to Hajj Umar Saidou Tall, who was a West African political leader and founder of the Toucouleur empire. In Figure 2, French Prime Minister Edouard Phillipe is shown returning the sword to the President of Senegal Macky Sall.

Final considerations

In the current situation, some efforts can be considered to change the current scenario, such as (1) cooperation between legislative powers and members of scientific societies to discuss the creation of effective laws for the removal and production of bibliography regarding paleontological specimens; (2) diplomatic dialogue between countries to reach consensus on historical-cultural reparations; (3) certification of existing artifacts made of ivory to differentiate them from new products; and (4) international cooperation between National Police Agencies together with Interpol to dismantle criminal organizations.

Therefore, discussions about geoethics must be expanded and disseminated in all countries. Efforts are being made in Brazil, driven by the Brazilian Society of Geology (SBGeo) through the Geoethics Commission, and also by students from the Student Chapters of the Initiative on Forensic Geology (IUGS-IFG), where they recently published a conference summary at the 50th Brazilian Geology Congress presenting the importance of discussing the topic and its relevance for society.

Gustavo Schmidt Cabral

Graduate student in Geological Engineering at UFPel. Founder and current President of the UFPel IFG Student Chapter.

Larissa Bergamini Santos

Graduate student in Geological Engineering at UFPel. Founder and former President of the UFPel IFG Student Chapter.

References

MENEZES, Paula Santos; ÁLVAREZ, Estefania Piñol. A descolonização dos Museus e a restituição das obras de arte africanas: o debate atual na França. CSOnline-REVISTA ELETRÔNICA DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS, n. 29, p. 23-23, 2019. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.34019/1981-2140.2019.26686

UNESCO, 2020. “MUSEUMS AROUND THE WORLD: IN THE FACE OF COVID-19”. Disponível em: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373530.locale=en RAJA, N.B. et al., 2021. Colonial history and global economics distort our understanding of deep-time biodiversity. Nat Ecol Evol (2021). Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01608-8

DUFFY R. et al., 2015. Toward a new understanding of the links between poverty and illegal wildlife hunting. Conserv Biol. 2016 Feb;30(1):14-22. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12622. Epub 2015 Nov 23. PMID: 26332105; PMCID: PMC5006885. LOCHSCHMIDT, M. F., 2013. Marfins orientais: sincretismo artístico e dinâmicas de mercado. Ecossistemas Estéticos: Belém, Brasil. Disponível em: http://anpap.org.br/anais/2013/ANAIS/simposios/10/ Maria%20Fernanda%20Lochschmidt.pdf

BARBOSA, V., 2019. O fim da “Rainha do Marfim” – do lucro com massacre de elefantes à punição. Revista Exame. Disponível em: https://exame.com/mundo/o-fim-da-rainha-do-marfim-do-lucro-com-massacre-de elefantes-a -punicao/

HSI, 2007. Ivory Trade and CITES. Disponível em: https://www.hsi.org/news media/african_ivory_trade/

BALE, R., 2018. Entra em vigor lei que proíbe comércio de marfim na China. National Geographic. Disponível em: https://www.nationalgeographicbrasil.com/animais/ 2018/01/entra-em-vigor-lei-que-proibe-comercio-de-marfim-na-china

DAYO, A., 2022. France Returns 19th Century Historic Sword to Senegal. The African Exponent. Disponível em: https://www.africanexponent.com/post/4531-france-returns-19th-century-sword-of senegalese-scholar

CABRAL, G. S. et al., 2021. INITIATIVE ON FORENSIC GEOLOGY STUDENT CHAPTERS: RELEVANCE IN THE BRAZILIAN SOCIAL CONTEXT. In: 50º Congresso Brasileiro de Geologia, 2021, Brasília. Anais do 50º Congresso Brasileiro de Geologia, Volume 2. Brasília: Sociedade Brasileira de Geologia – SBG, 2021. v. 2. Disponível em: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353391088_INITIATIVE_ON_FORENSIC_GEOLOGY_STUDENT_CHAPTERS_RELEVANCE_IN_THE_BRAZILIAN_SOCIAL_CONTEXT

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email